I rewatched Eric Rohmer’s Conte de printemps (A Tale of Springtime) this week.

I was searching, I think, for some tangible confirmation that spring exists in actuality instead of merely in abstraction. This winter here in London was grey. And when I say grey, I mean grey with all of its metaphoric baggage: barren, uninteresting, sad, lifeless, tedious, unrelenting. I spent a lot of this winter attempting to work through the grey – and failing miserably. This was my first true London winter and, for the first time in my life, the seasons changed not in accordance with a school schedule, but rather of their own volition. Of course, the seasons have never actually been concerned with my Google Calendar and exam deadlines. And yet, this year, the change from autumn to winter caught me unaware.

Winter felt an adversary whose effectiveness lay in indifference. No matter how much time I spent attempting to carve out routine and meaning, winter answered with its unrelenting apathy (Boats borne back ceaselessly, etc., etc.). I kept thinking of winter two years previous when I was attempting to navigate (survive) the 2021-22 winter lockdown in my dorm room at Oxford, subsisting exclusively on takeaway coffees and daily Strava updates. That winter I got really into long-distance running. But I also got really into what your favourite nineteenth-century heroine might call ennui.

Ennui is described as a feeling of listlessness and dissatisfaction arising from a lack of occupation or excitement. It is a French loanword which originally comes from the Late Latin word inordiare (“to make loathsome”), a word which also gives us our modern annoy. Listlessness and dissatisfaction perfectly characterize the monotony of that winter. But loathing is equally accurate. It wasn’t that I spent hours actively hating where I was or what I was doing (or not doing). It was rather that life was made loathsome through my own listlessness.

So - what do I mean by that? I mean that we need to talk about philology some more (sorry). Inordiare is the Latin negation of the verb ordinare meaning “to arrange, to set in order, to organize or to adjust”. This idea of organization was central to my own (and likely your) experience of the pandemic. Routines and regulations were upended, made useless and inconsequential. It didn’t matter if I woke up at 6 AM or 12 PM, left my room or stayed in bed - so long as I submitted my weekly essay by Wednesday night.

And so, not only does inordinare present us with the idea of loathsomeness but, at its root, inordinare’s conception of abhorrence derives from a lack of adjustment, or organization. Something is made loathsome from an innate absence of order. Which is exactly my own experience of my first Oxford winter. Life’s lack of structure and my inability to adjust to the nothingness left me listless and indifferent, filled with ennui.

It was this same ennui that reared its loathsome head this past winter. London was grey and suffocating and largely uninteresting. I found it hard to be excited about yet another week spent doing the mundane things that make up life. This all sounds very existential, I know. But all I really mean is that going to big Tesco felt like the most exciting part of most of my days. This – along with some intense job applications – has meant a distinct lack of letters over the past month.

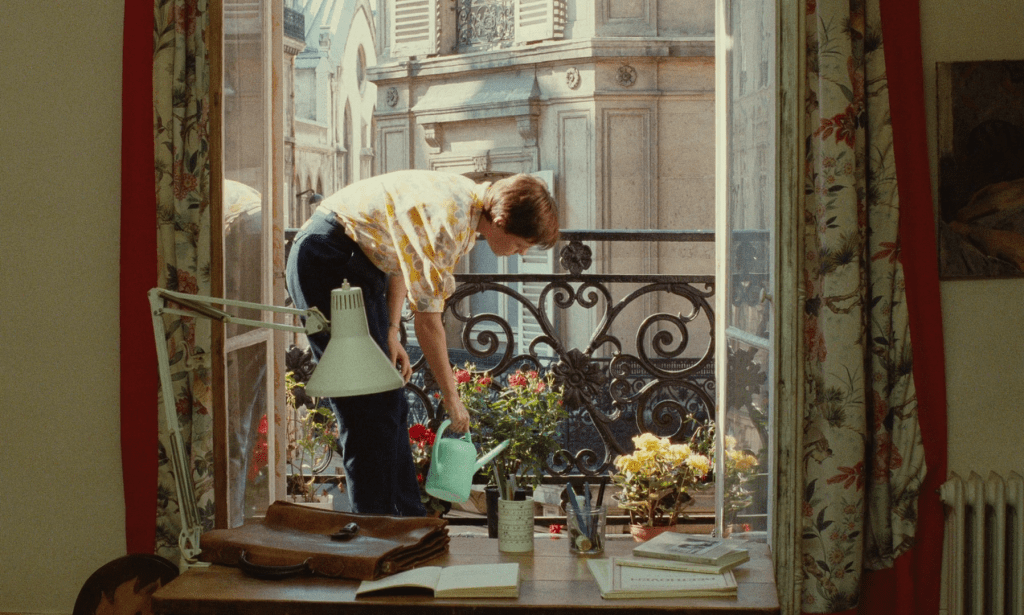

Now nearing the end of March, I knew I needed to reach outside myself to find some tangible reminders that winter is indeed over. One of my favourite reminders is Eric Rohmer’s Conte de printemps (A Tale of Springtime), the first film in his ‘Tales of the Four Seasons’ quartet. The film captures that feeling of latent expectation, of both the self and the season attempting to regulate and order (ordinare) itself into something more inviting. Jeanne, a high school philosophy teacher, strikes up a conversation with Natacha at a party in Montmorency. The two go on to interact with Gaelle, Jeanne’s cousin, Igor, Natascha’s 40-year-old bureaucrat father, and his 20-year-old girlfriend, Eve.

Vacillating between the French countryside and a rotating roulette of beautiful Parisian apartments, the story bears out its title with overlapping portrayals of budding love. As springtime flowers begin to blossom, characters find themselves caught between their thoughts and feelings. Individual convictions are challenged by the messy reality of how love takes hold. Nobody wants to give in to the natural rhythms of life and love – rather, everyone is constantly attempting to force things to happen. This is obviously a fruitless endeavour with the characters learning that false hopes and surprises are as common romantically as they are meteorologically.

What I love about this film (and the rest of Rohmer’s filmography) is his ability to remind you that your most mundane problems are worth exploring with careful consideration. Everyday interactions become plot points in Rohmer’s cinematic microcosm. The smallest word or gesture becomes the spark that could alter a character’s life and send in careening in a different direction entirely. Dinner dialogue becomes an opportunity to contest beliefs, a walk becomes a confrontation of thoughts and feelings. Characters are brought together because of their disparate flaws, not in spite of them, before splintering off again in different directions, their fates eternally altered.

Watching Conte de printemps this spring, I was reminded that my own winter ennui is – in the best possible way – mundane. Feelings of winter lethargy and listlessness are universally common, as are the unmitigated hopes we often place on the advent of spring. What Rohmer captures so brilliantly is the value in such emotions. Characters are interesting because they are often erratic, contradictory, and uncertain in their beliefs and feelings. Large revelations are unheard of and largely uninteresting to Rohmer. Rather, characters are simply allowed to discuss the questions that arise from the mundanity of love and life. And rather than hindering it, it is mundanity that drives the plot forward – a reassuring reminder as I move from winter to spring.

It is reassuring to be reminded that the grey fog of an uninteresting winter would, if captured on film, be exactly the type of story I would love to watch. So here’s to spring, even if it as equally uninteresting.

With love : Avery