Casa Malaparte: Fascism, frescoes, and the French New Wave

Inside Capri's architectural curiosity

Welcome to another December letter.

In recent news, it snowed here in London on Sunday. My neighbourhood did in many ways remind me of the Bruegel scenes I discussed last week - although with (sadly) less rudimental ice hockey as the Thames did not have the courtesy to freeze over.

Since last week leaned into the winter weather, I thought this week could instead celebrate some Mediterranean escapism. And since I haven’t yet dedicated a letter to an exclusively architectural topic I thought it about time to spend a few hundred words waxing poetic about some obscure building that few of you have likely heard of/care about

But that is the joy of Artifex! I have a few minutes to convince you to care - or if not to care, then at least to leave these letters with a bemused respect for art and its makers.

Today’s letter is about one such maker. Although perhaps respect might be too kind an adjective to attach to Curzio Malaparte. Or perhaps not. Malaparte was indeed a formidable character whose fascistic tendencies were merely one facet of the Italian writer, filmmaker, war correspondent, and diplomat’s immensely individual life. So yes, perhaps respect of the slightly more solemn variety is apt.

Curzio Malaparte was born Kurt Erich Suckert in 1898 in Tuscany, the son of a German father and his Lombard wife. He was educated at Collegio Cicognini in Parto and La Sapienza Univesity in Rome before beginning a career as a journalist. Malaparte went on to fight in World War I before returning to Rome to participate in Mussolini’s March on Rome in 1922. Throughout the 1920s Malaparte went on to found numerous literary journals, periodicals, and newspapers often in support of the Partito Nazionale Fascista of which he was an active member.

Notably, in 1925, the writer changed his given name from Suckert to Malaparte as a play on Napoleon’s family name “Bonaparte” which means “good side” in Italian. “Malaparte”, consequently, means “evil/wrong side” - an apt metaphor considering Malaparte’s political tendencies of the time.

Malaparte's eponymous villa, located on the tiny isle of Capri, was conceptualized and constructed in large part due to Malaparte’s literary critiques. In 1931, Malaparte authored Technique du coup d’Etat, a book which set out to study the tactics of the coup d’état focusing on the Bolshevik and Italian examples. The same book also included a chapter titled A Woman: Hitler which openly critiqued Hitler as a reactionary and insufficient leader. This (unsurprisingly) led to Malaparte being stripped of his National Fascist Party membership and sent to internal exile from 1933 to 1938 on the island of Lipari

While Malaparte was freed from this first confinement by Mussolini’s son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano, he went on to be arrested and confined again in 1938, 1939, 1941, and 1943 in Regina Coeli, Rome’s primary jail. During this period, Malaparte began to design and build Casa Malaparte with the ever-optimistic hope that further imprisonments might be undertaken from Capri’s rocky coastline instead of a barred Roman cell. Malaparte’s partner for the project was noted Italian modernist architect Adalberto Libera.

Libera was a talented and innovative architect at the time, having helped to found the M.I.A.R (Movimento Italiano per l'Architettura Razionale or “Italian Movement for Rational Architecture”). Through MIAR, Libera was invited by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe to the 1927 Stuttgart Exhibition and went on to organize MIAR exhibitions in Rome in tandem with the Fascist regime. Libera’s personal role as founder and secretary of the group allowed the young architect to establish a close working relationship with high-ups of the Fascist regime in Rome; these connections granted him and Malaparte permission to build their villa.

In beginning to design Casa Malaparte, Libera’s personal inclination towards both Futurism and Rationalism is apparent. Libera attempted to combine a stripped-down Modernism with a fascist sensibility all while incorporating classical archetypes. According to Malaparte, Libera desired “sincerity, order, logic and clarity above all”, desires which are borne out in the building’s volumetric form and symmetrical planning.

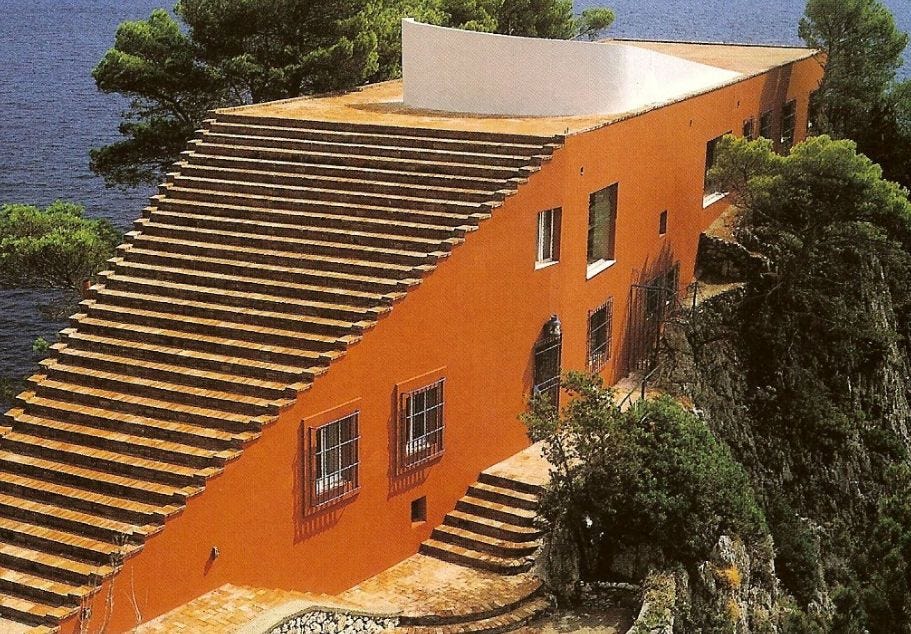

However, this paragon of 20th-century modernist architecture was not simply Libera’s creation. Rather, the plans submitted by Libera for approval to the Capri authorities in March 1938 were never completed and only form the foundations of the eventual building. Malaparte himself had decided that his own visions for his seaside sanctum were to take priority. Building on Libera’s plans for a two-story, elongated rectangular building that stepped up in section toward the sea, Malaparte went on to add the home’s most distinct features.

It was he who insisted on the stepped roof design which takes inspiration from ancient Greek theatre seating which is set into the landscape. Malaparte also chose the villa’s distinctive red colour which was inspired by the Roman interiors found at nearby Pompeii and commissioned a set of furniture made of discarded Roman marble and wood meant to echo the forms of classical architecture. Similarly, the roof terrace’s white sculptural partition was the writer’s later addition.

These changes were instigated by Malaparte but found form through his builder, Adolfo Amitriano who oversaw Malaparte’s many changes to the site. These changes capture Malaparte’s more poetic, surreal sensibilities as not only an artist but also a writer. His brutal war reportage was known for blending truth with fantasy in a manner similar to the magical realist autobiographical short stories that Malaparte published during the period of the villa’s construction. Compared to Libera’s minimal rationalism, Malaparte’s finished vision feels like a contradiction caught somewhere between fact and fantasy.

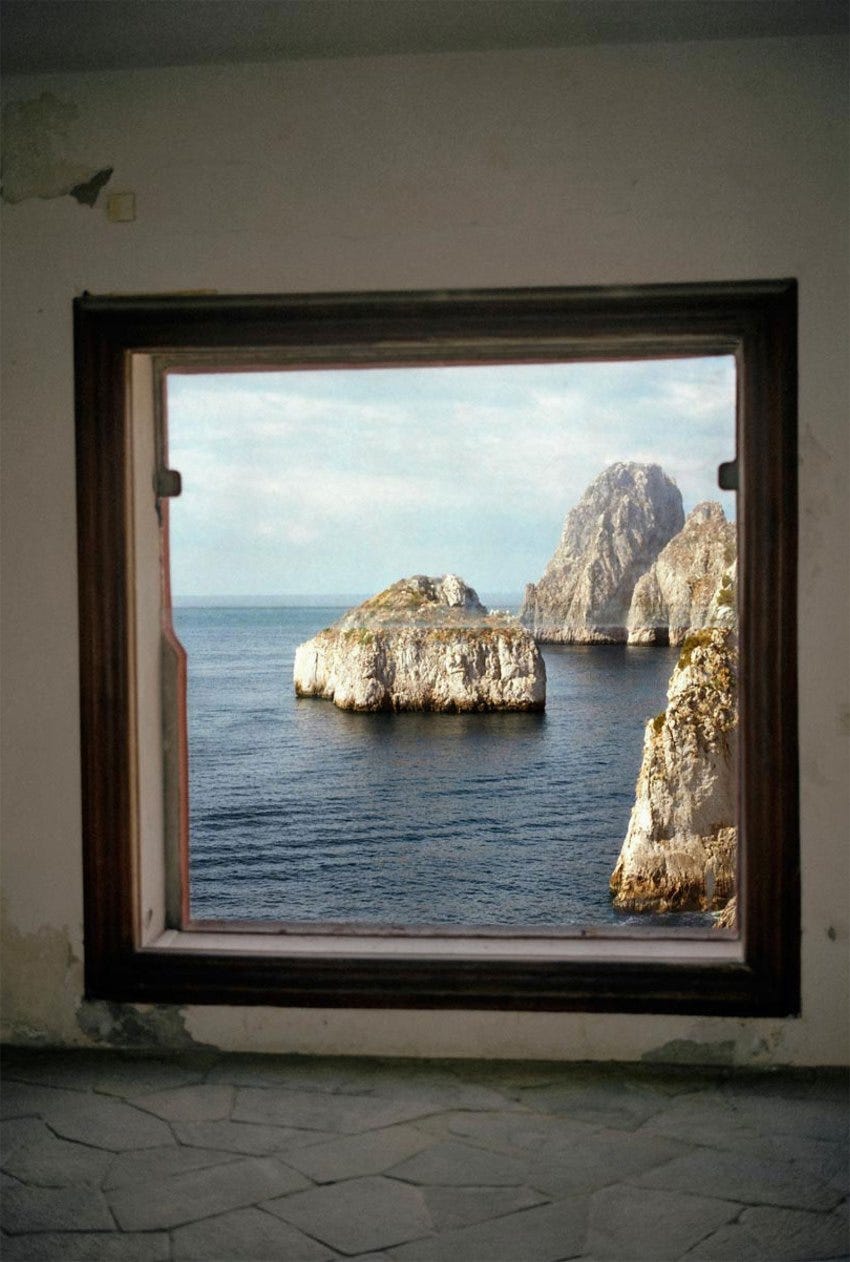

The red colour of the house as well as its stark interiors reflect such a paradox. On the one hand, the building is not the typical Modernist white which would help it stand out from its natural seaside surroundings. However, the red remains a foreign intrusion on an island setting characterized by blues, browns, and greens. Contrastingly, the architectural quality of the rocks is brought inside the villa as windows on the southwest facade were framed with a “braid of tufa stone” and larger furniture pieces were carved out of the local geological offerings.

Such contradicting elements allow for a slightly surrealist quality to pervade the entirety of the home. The large windows in the living seem to mimic paintings with their dark wood frames which transform the setting into a gallery whose eternal exhibition is the searing blue sea. Surrealism pervades even the simple hearth, whose flames are to be viewed in front of a small opening to the ocean, fire and water brought carefully together.

These are the elements that create the backdrop to Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 film Le Mépris (“Contempt”). Set on Capri and filmed partially at Casa Malaparte, the film follows a successful young French playwright, Paul Javal (played by Michel Piccoli), who accepts an offer from the vulgar American producer Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance) to rework the script for German director Fritz Lang’s film adaptation of The Odyssey. Paul’s wife Camille (played by Brigitte Bardot) accompanies him to Capri where layered personal and artistic conflicts ensue.

The enigmatic premise of a film within a film is set perfectly against the beautiful but crumbling home of Malaparte where past and present seem to coalesce. Bardot’s self-aware sensuality is echoed in the villa’s open lines and bold colours while the mythical landscape becomes a setting not simply for Homer’s ancient fable but also for Paul and Camille’s ruinous marriage. Le Mépris is a monument of French New Wave filmmaking, where experimentation and existentialism take centre stage. It is no wonder, then, that Godard chose Casa Malaparte as his filming location as the villa itself stands as a testament to those same qualities.

After Malaparte’s death in 1957, the house was abandoned and neglected before eventually being donated to the Giorgio Ronchi Foundation in 1972. The foundation funded serious renovations in the late 1980s and early 1990s overseen by Malaparte’s great-nephew, Niccolò Rositani. Much of the original furniture survive simply due to its immense size while Malaparte’s bedroom and book-lined study miraculously remained intact through the decades of neglect. The careful restoration has allowed the original vision of both Malaparte and Libera to be brought back to life.

This vision was perhaps captured best by the avant-garde architect John Hejduk in a 1980 edition of Domus magazine (once the international publication for Italian fascist-rationalist architecture). Hejduk wrote: “Libera’s Malaparte house is private. It is a house of paradoxes. It is an object which consumes. It is filled with unrequited histories. It is a relic left upon the pinnacle after the seas have subsided. It is a sarcophagus of soft cries. It whispers of inevitable fates.”

Hejduk’s description of Capri’s architectural curiosity is spot on: Casa Malaparte is simultaneously mythical and resolutely modern.

With love: Avery