Weekly Design Roundup – Korean brutalism in Berlin, contemporary classicism in London, and French modernism in Indiana

🌀🌀🌀 Globetrotting through Berlin, London, Veneto, and Columbus, Indiana on an architectural expedition

This week delivers an architectural special on my ⋆ .𖥔˚Weekly Design Roundup˚𖥔. ⋆

꩜꩜꩜ This email is likely too long to read in your inbox - open the post in a web browser to read the entire thing!

I decided to follow my architectural intuition this week and report exclusively on a variety of homes, villas, castles, and other oddities that I have stumbled across over the past week-ish. I have been hosting one of my best friends and her partner this month in London and their exploration of London has instigated some hitherto unknown Wikipedia deep dives and frenetic Google searches - all of course detailed below. I love the way that an outsider’s perspective helps me reevaluate my own city; questions arise that I don’t have the answer to and suddenly an entire Substack post has practically written itself.

I hope you enjoy said post, sent to you directly from a very muggy London.

Christine Sun Kim’s brutalist Berlin apartment

First on the tour this week is Christine Sun Kim’s heart-stopping brutalist apartment in Berlin. I fell in love with her space thanks to, of course, The World of Interiors on Instagram which posted a feature of the artist and her home. I really should be adding a World of Interiors sponsorship logo of some kind to Artifex considering how many features originate from their feed…

Okay but who is Christine Sun Kim? She is an American sound artist, performer and activist based in Berlin. She also happens to be deaf, a fact which informs her artistic output. She is concerned primarily with how sound operates in society and explores questions of language, marginalisation, communication, and belonging through drawing, performance, and video.

Her apartment in Berlin is a testament to her own artistic eye as well as her Korean heritage. The home is found in the 1970s high-rise Leipziger Straße Complex, a construction seen as an icon of postwar modern architecture. Kim and her husband, the conceptual artist Thomas Mader, renovated the home in 2022, rearranging walls, pouring resin floors, and designing details that reflected their international heritage.

My favourite example of this blending of roots are the shoji sliding doors found throughout the home. The doors, inspired by the Katsura Imperial Villa’s tea house that designer Rio Kobayashi saw on a visit to Japan, create a much more open space when tucked away while still allowing for privacy when closed. The structure of the doors 'reflects Kim’s Korean heritage, ‘whereas the intricate pattern – inspired by the blue-and-white Bavarian flag – is a nod to her husband’s birthplace.’

Like her home, Kim’s art also reflects her preoccupation with history, belonging, and personal identity.

Her latest exhibition, 1880 THAT, interrogates the concept of language as a home – asking, what does it mean to live with the threat of losing one’s language? Through installations by Kim and her husband […] it highlights the fundamental right to communicate, especially at a time when sign language is under threat (due to a lack of resources, funding and education). For example, in the UK, though BSL is the first language of 87,000 people, it still lacks full legal status, hindering access to essential services.

1880 THAT is currently on at the Wellcome Collection here in London until Nov 16 2025 while another exhibition, Christine Sun Kim: All Day All Night, is on at the Whitney Museum of American Art in NYC until July 6. Go see one of them if you can!!

Miller House & Garden in Columbus, Indiana

Spring here in England means one suddenly develops a sudden and involuntary preoccupation with gardens. The Royal Horticultural Society of course hosts the Chelsea Flower Show each Spring here in London on the grounds of the Royal Hospital Chelsea. Cherry blossoms and roses abound both in the city and countryside as Spring rears its pink head. And Instagram feeds are inundated by examples of gardens extraordinaire, English or otherwise.

One of these examples was brought to my attention thanks to T Magazine’s list of 25 Essential Gardens to See in Your Lifetime, a delightful list that required six horticultural experts ‘to nominate 10 must-see gardens and, on a video call in March, they spent almost four hours winnowing down that long list to a definitive 25.’

One of the gardens that made the final cut was the garden at the Miller House and Garden in Columbus, IN - not not Ohio. Now I had heard of the Miller House many times, most notably thanks to the near-perfect film Columbus, written and directed by Kogonada. For a bit of context, the film follows John Cho, the son of a renowned architecture scholar as he gets stranded in Columbus, Indiana, and strikes up a friendship with a young architecture enthusiast, Haley Lu Richardson.

The film’s real protagonist, however, is the titular city of Columbus, a city of only 50,000 but which is internationally recognised for its publicly commissioned works of mid-century modern architecture.

One of these commissions is, you guessed it, the Miller House and Garden. The architect Eero Saarinen designed the home for midwestern industrialist J. Irwin Miller, and his wife, Xenia in 1953. The approximately 7,000-square-foot, flat-roof glass-and-stone family home builds on the architecture of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and epitomises the international Modernist aesthetic.

Buuuuut, back to gardens. Alongside the home, the Millers also wanted a garden and it was Saarinen who hired Dan Kiley, a regular collaborator of his, to design the outdoor space of the Millers’ home. What continues to makes Kiley’s landscapes so striking is his choice to pair Saarinen’s modernism with traditional 17th-century French-inspired gardens.

Saarinen and Kiley’s marriage of classical formality and innovative Modernism is gorgeous - and I’m not just saying that as yes, the combination is perfectly suited to my particular tastes. Kendra Wilson explains:

[Kiley] lined the entrance drive with a double row of horse chestnut trees (since replaced by yellow buckeyes) and added another allée, of honey locusts, along the west side of the house to frame the river view. Magnolia trees by the entrance add curves to the symmetry, while large, free-flowing weeping beech trees shield the house from wind and sun. The sense of control is mixed with exuberance: By the terrace, the emerald green lawn meets platforms of liriope and a checkerboard with pink and red impatiens under a canopy of crab apple trees, all of which evokes the decorator Alexander Girard’s vibrantly patterned interiors

The lined walks and careful symmetry of Kiley’s grounds feel like a careful adaptation of Saarinen (and van der Rohe’s) straight lines and careful composition. Or the adaptation is the other way around. Regardless, I love the deliberateness of both the garden and home at the Miller House.

As I write this, I recognise that the careful intention behind both 20th-century Modernism and 17th-century jardins à la française likely reflect my own tendency towards studied naturalism. That feeling, in a piece of design – whether it be a home, a garden, a piece of furniture – that the effortlessness that appears in the finished product is a result of intense contemplation, deliberation, and exertion.

The Miller House and Garden captures that feeling. If you find yourself in Columbus, IN any time soon, please let me know so I can live vicariously through you. But, if you, like me, will not find yourself in the Hoosier state any time soon, I cannot recommend watching Columbus, the film, enough.

Quinlan Terry villas in Regent’s Park

Next, something closer to home.

As mentioned, some of the topics this week have been inspired by my friend Alyssa and her partner Jake’s experience of London these past weeks. One of these experiences was, excitingly, their engagement in a quiet corner of Regent’s Park. And the subsequent engagement photos featured a gorgeous backdrop of lush foliage and classical architecture.

Regent’s Park is known for its classical villas and row houses that both surround the enclosed park and are found within the space on its various lakes and canals. When I first lived in London, I lived just east of Regent’s Park and spent many an evening running around its wooded paths, marvelling at these classically inspired homes.

It was not, however, until this week, prompted by Alyssa and Jake’s engagement, that I actually Googled “Why are there so many classical villas in Regent’s Park?”.

The answer, it turns out, is complicated.

The story starts with a man named John Nash who was born 1752 and became one of England’s most renowned architects and city planners. Working during the Regency and Georgian periods, Nash designed many notable areas of London and Brighton in his (and period’s) characteristic Neoclassical and picturesque styles (the Royal Pavilion, in Brighton as well as Marble Arch and Buckingham Palace in London number among his designs).

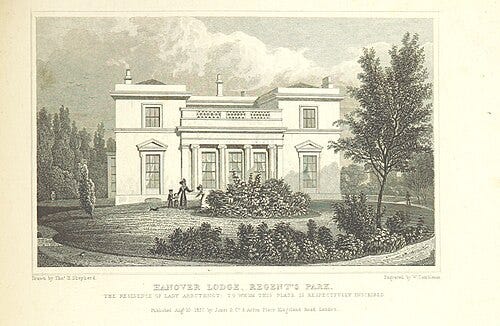

Another of Nash’s famed developments was Regent’s Park, a royal estate in northern London turned into both a park and residential area named after Nash’s official patron, George, the Prince Regent. Part of Nash’s design included plans for 48 individual villas (as well as a royal palace!) dotted throughout the park grounds. Only a handful of these, however, were built according to Nash's original designs, the most notable being Hanover Lodge and St John’s Lodge, before 1826 when work on his scheme was stopped by the government.

While St John’s and Hanover Lodges are, of course, beautiful, but neither they nor Nash’s other constructions back on to Regent’s Canal, the place where, running six years ago, I first noticed a row of enormous villas and became aware of the park’s Neoclassical character. So whose villas were those?

Turns out they are also, at least in spirit, John Nash’s.

In 1987, after Bedford College moved from Regent’s Park having merged with Royal Holloway, the Regent’s Park's Crown Estate Commissioners commissioned the Neoclassical English architect Quinlan Terry to build six detached villas that echoed Nash’s original architectural plans. Terry apparently said in a 2002 interview that the Crown Estate had told him to ‘step into Nash's shoes and carry on walking’.

The villas were built between 1988 and 2004 in the northwest corner of the park, backing onto Regent’s Canal (bingo!). Terry designed six houses each in a different classical style, intended to represent the variety in classical architecture: the Ionic Villa, Veneto Villa, Gothick Villa, Corinthian Villa, Regency (or Tuscan) Villa, and the Doric Villa.

The playful nature of all six of Terry’s villas, using slightly different classical styles to express Nash’s original aspirations, feels both fantastical and deeply reverential. I’m sure, to Terry, getting the commission must have felt like an architect’s pipe dream – to build a series of new homes with a nearly unlimited budget whose only requirement is to capture the essence of one of your field’s greats.

A history of Neoclassicism come full circle.

Finally, a tour of some Strawberry Hill Gothic

A quick final London pitstop to finish our architectural tour.

In researching Terry’s villas, I was struck by his use of ‘Gothick’ with a ‘k’ to distinguish the architectural vernacular of his villa from that of traditional Gothic architecture.

Upon further investigation, I learned that the early period of the Gothic revival movement in England is sometimes called Gothick which distinguishes it from the later Victorian Gothic Revival. It is also seemingly a term used deliberately to separate certain ‘Gothically-inspired’ structures from the strict range of principles which govern scale, proportion, construction and detail in traditional Gothic architecture.

Regardless of the term’s slightly murky meanings, the heyday of early Gothic(k) Revival architecture in England was between 1730-1780 with the best example being Horace Walpole’s house in Twickenham, south-west London.

London is, of course, famous for its Gothic Revival architecture. Think Big Ben, the Houses of Parliament, the Royal Courts of Justice, St Pancras Hotel, and Tower Bridge.

One of the wildest and earliest examples of London’s Neo-Gothic boom, however, is Strawberry Hill House.

Strawberry Hill House was designed by English writer, politician, and antiquarian, Horace Walpole, who was son of the first British Prime Minister, Sir Robert Walpole.

Horace Walpole rebuilt the existing house in stages starting in 1749 with subsequent additions happening in 1760, 1772 and 1776. These added Gothic features such as the distinctive towers and battlements on the exterior of the home as well as elaborate Medieval-inspired interior decoration and finishings (lavishly documented in this House and Garden article).

Walpole's 'little Gothic castle' is mind-numbingly beautiful in its detail but, more significantly, is one of the most influential individual 18th-century buildings which prefigured the later Gothic Revival architectural movement. Basically, Walpole did it first - or came close to. The ornate decoration and fantastical interpretation of this early style Gothic(k) architecture is equally known as Strawberry Hill Gothic.

Strawberry Hill Gothic! What a name!

I will finish this section with a final piece of analysis on Strawberry Hill House, done by the incredible Holly James Johnston, a writer, presenter, performer, and academic currently completing a PhD at Oxford.

Holly spoke recently on BBC 3’s programme discussing the Queer Gothic, covering Strawberry Hill House in particular. Holly’s analysis on how Walpole’s home can be read as a ‘queer architectural rebellion’ can also be found on the RIBA website.

Go give it a read, go give Holly a follow, and go visit Strawberry Hill House yourself!

That’s it for this week! ꩜꩜꩜Avery

I am kicking myself for not having visited the J Irwin Miller House yet!!

I want to skip through the gardens, sit in the conversation pit, and soak up all of the Girard-ness. This is the project that resulted in the birth of the Eames Aluminum Group chairs!!

Crazy to have Saarinen, Girard, Eames, and Kiley together on one project. ❤️

Thanks for sharing all of these spots!