DISPATCH FROM: The Basque Country

📮 A tour through the architectural, artistic, typographic, and sporting history of the beautiful Basque Country

A slightly delayed postcard, coming to you after a lovely holiday in the French Basque Country

꩜꩜꩜ This email is likely too long to read in your inbox - open the post in a web browser to read the entire thing!

Another (very long, I know!) Dispatch From, this time recapping my time spent in the south-west of France in the Basque region, one of my favourite places in the world.

This letter is slightly later than I intended due to a combination of being struck down with a nasty flu/cold for the better part of a week and also simply wanting to take some proper time off to enjoy a holiday with Will’s (my partner) family.

Will’s parents have a home in Hossegor, a small surf town in the southwestern area of France that they have owned for the last couple decades. Will grew up partly in Paris and the family’s Basque home became the centre of his childhood summers and holidays. He and his brother grew up surfing, swimming, playing tennis, and golfing in the lush pine forests and wild Atlantic coast distinct in the area around Biarritz.

When Will and I started dating a few years ago, one of my very first travel requests was going and visiting the Basque Country which I understood still played a central role in the cadence of Will’s family’s life.

This enclave of history, architecture, culture, food, and language all seemed entrancing, particularly to someone who speaks French and had spent a good amount of time travelling around the rest of France over the years.

Years later, I have now collectively spent many weeks in this special corner of the world. Today’s newsletter is merely an introduction to some of the many pieces of history and design that make this region so extraordinary.

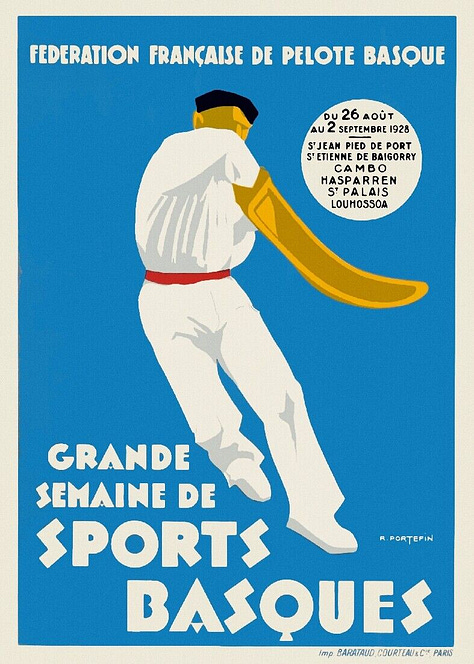

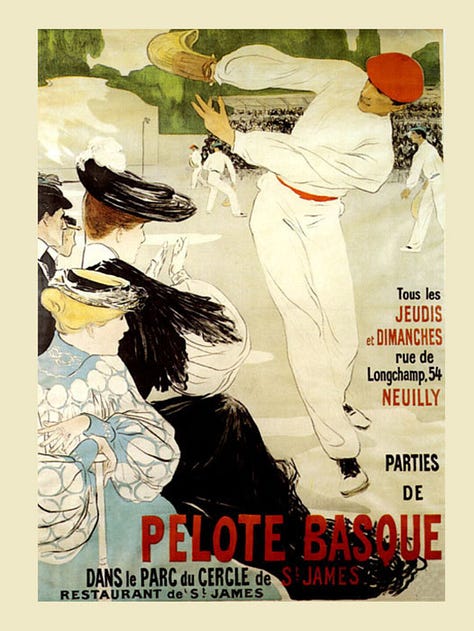

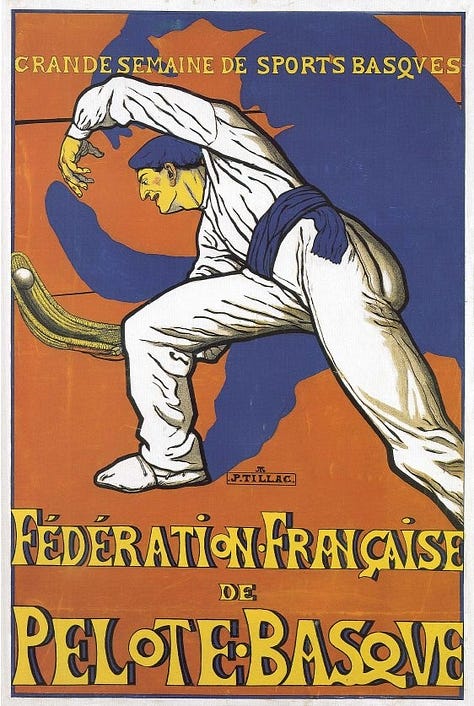

We’ll kick off our tour with some Basque Pelota

Okay, so I know sports isn’t usually the central topic of this newsletter, however you will all be pleased? shocked? to know that I am, at my core, a sports nut. A born-and-bred ice hockey devotee, I grew up playing a range of sports and in adulthood have continued both playing and watching many a sport.

My adult education has included becoming an expert in some otherwise unknown sports (read: cricket) but while visiting the Basque region I have loved getting to know some of the more niche regional sports, including pelota.

From Wikipedia:

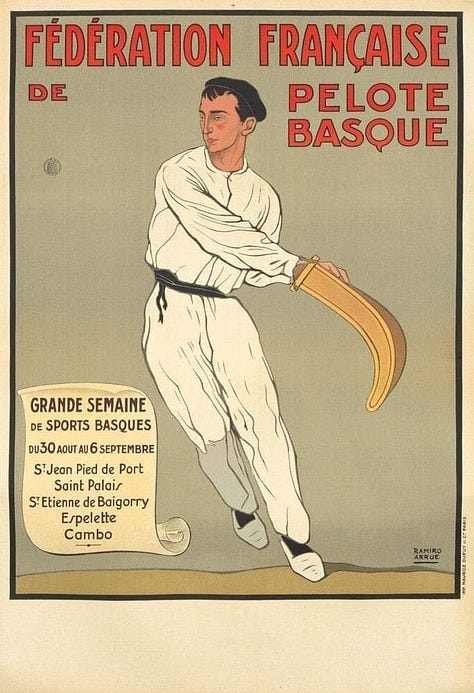

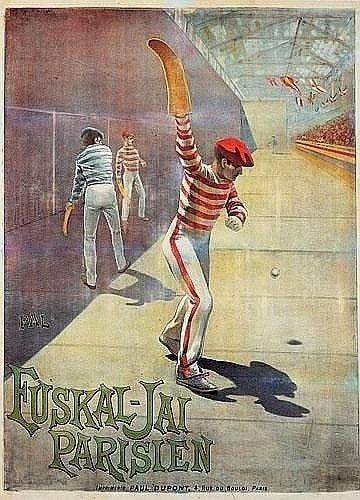

Basque pelota is the name for a variety of court sports played with a ball using one's hand, a racket, a wooden bat or a basket, against a wall (frontis or fronton) or, more traditionally, with two teams face to face separated by a line on the ground or a net.

The sport is hard to describe without visual aides, so below is a short video from 1975 of men playing a version of pelota using wooden baskets.

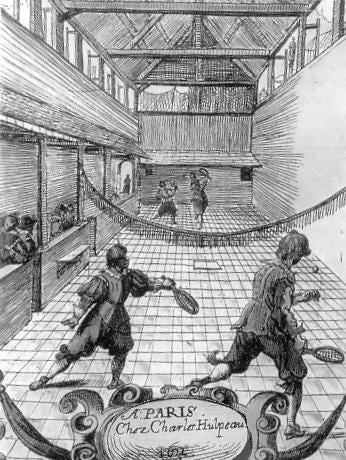

The origin of this type of wall-facing ball sport likely traces back to Greek and Roman ball games with the term pelota probably coming from the Vulgar Latin term pilotta (ball game). In modern times, the growth of pelota is linked to the decline of the ancient form of the game jeu de paume around 1700.

Jeu de paume, literally meaning ‘game of the palm’, was a ball sport where players hit the ball with their hands. In the late 17th and early 18th century, the game evolved into the modern jeu de paume which used racquets, eventually becoming what we know today as tennis. While most of Europe adopted the new racquet version of the sport, rural Alpine and Pyrenean communities retained the older hand-hitting form of the game.

So how does this strange sport intersect with design?

Pelota is ubiquitous in both the French and Spanish Basque regions and this ubiquity can be seen in the architecture and art of the area.

Remember that term fronton, referring to the wall against which a pelota ball is hit? Well these are often found in the open air, built right into the urban architecture of Basque towns, a style known as ‘frontons place libre’. Pelota frontons were – and are – not simply a sporting venue, but rather a gathering place for the entire town community. The open-air frontons were traditionally used as a place to celebrate religious events, civic festivals, and personal events like weddings and funerals. Today they are still used for traditional festivals as well as open-air concerts, events, and exhibitions.

The most striking example of this type of embedded communal architecture was in the tiny town of Biriatou right on the Spanish border.

Will and I’s pilgrimage to the town was instigated by my friend Kelsey who lives in the Basque Country herself and who celebrated her gorgeous Basque wedding at the Auberge Hirribarren, the inn in Biriatou which is tucked right next to the town’s fronton place libre.

Will and I had a magical couple hours enjoying a mouth-watering Basque lunch, meandering through Biriatou’s steep streets, and reading the historical plaques dotted around the town.

I am now desperate to go see a pelota game in person next time we’re down, but in the meantime I have been enjoying perusing frontons.net, an online database of pelota frontons around the world.

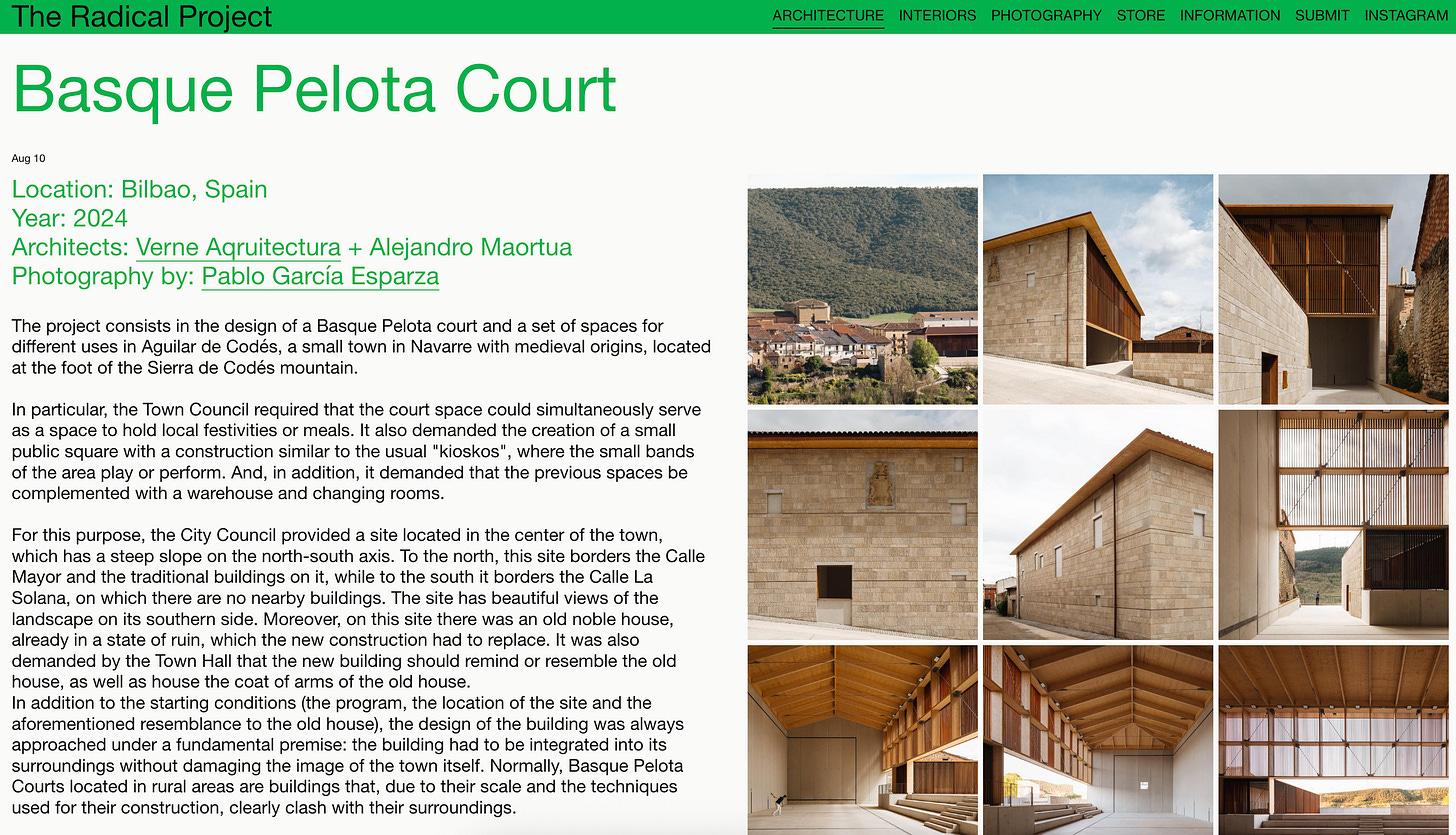

I have also been reading up at more modern interpretations of pelota courts throughout the Basque region, including this striking example from Bilbao which shows just how integral pelota still is to modern Basque architecture and culture.

Next, a discussion of Basque graphics and typography

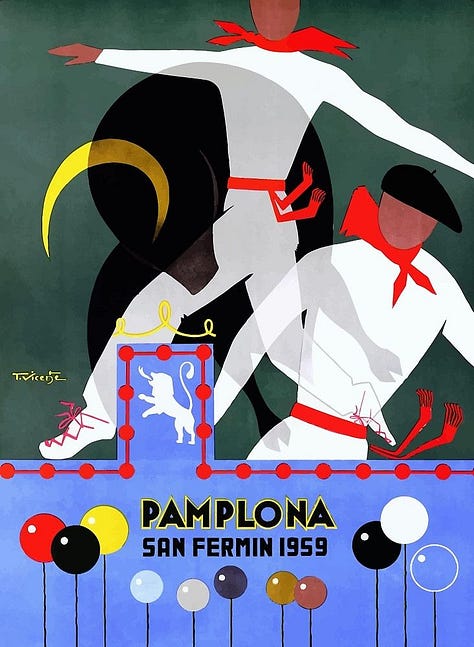

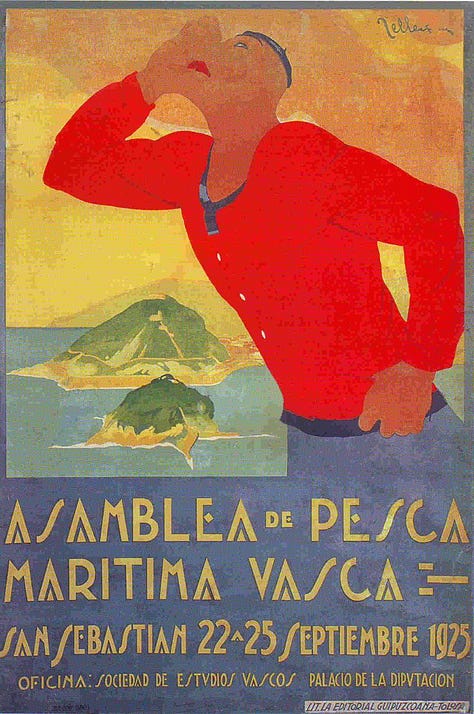

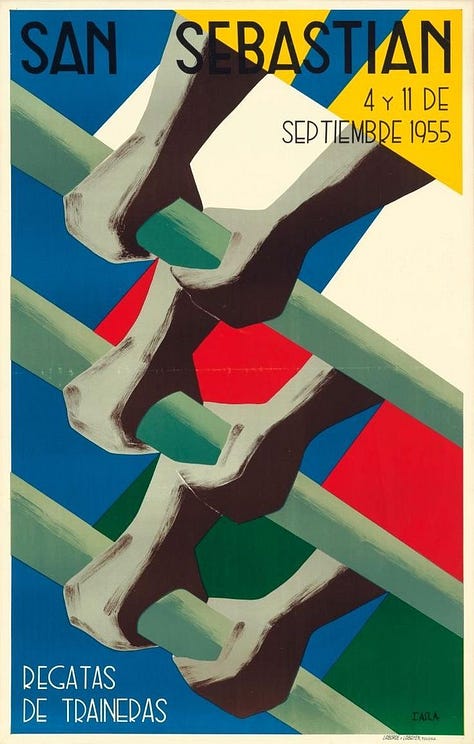

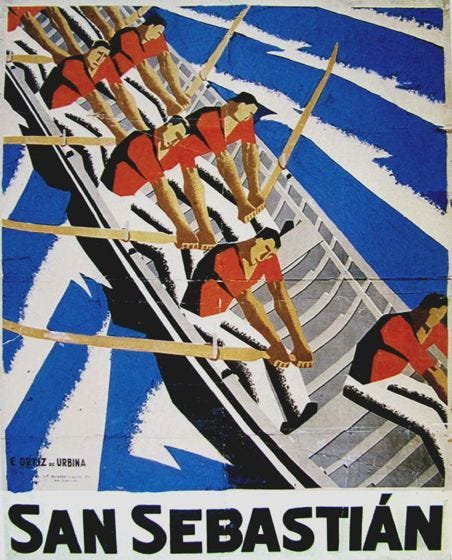

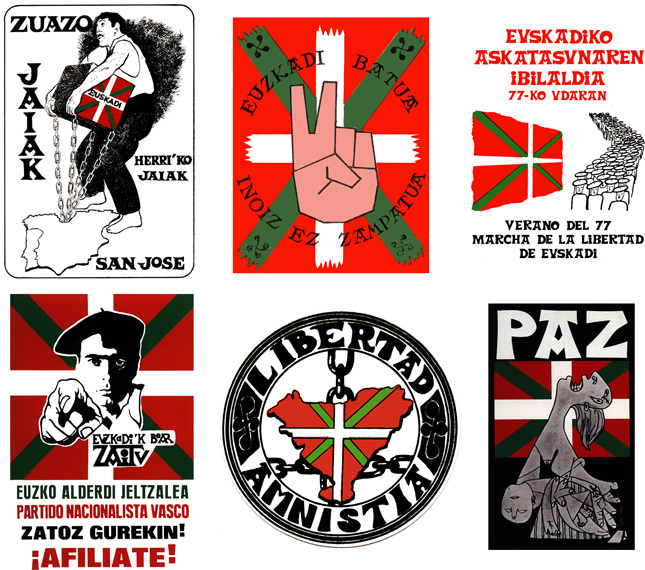

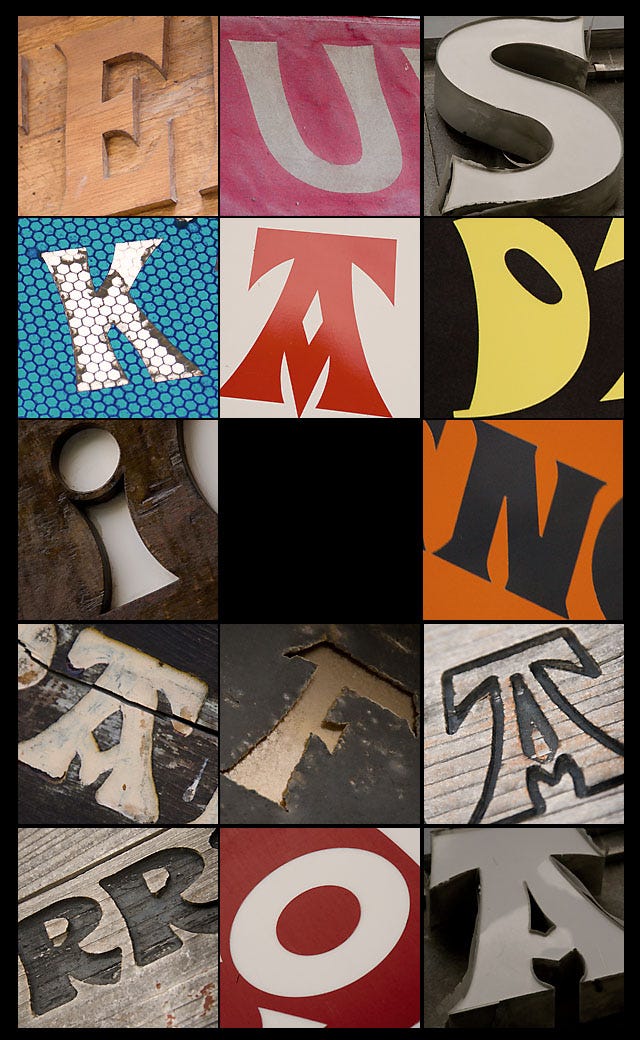

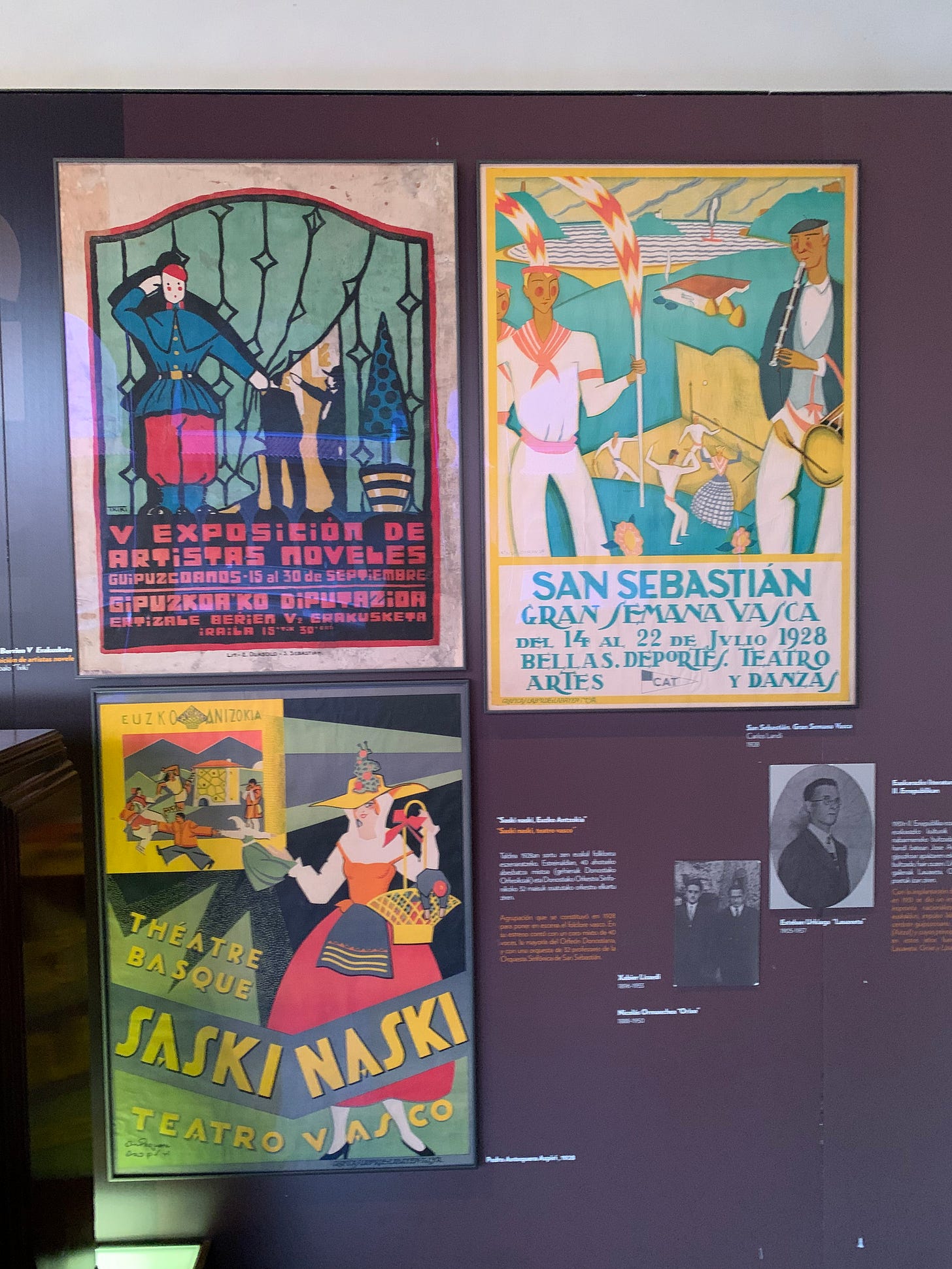

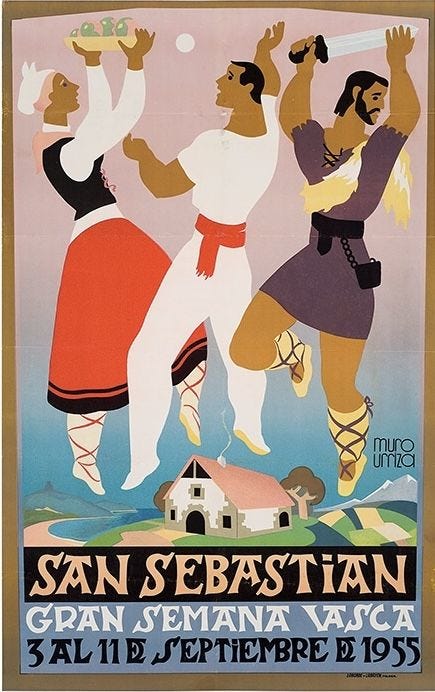

Relating to Pelota, since my first visit to the Basque region I have been struck by the distinctiveness of Basque typography and graphics. On a visit to the Musée San Telmo, the museum of the Basque society in San Sebastián, I was enthralled by the vintage and contemporary examples of posters relating to Basque sport, history, and culture.

Spending a bit of time on Pinterest searching for vintage Basque posters led me down the rabbit hole of the history of typography and Basque cultural symbols.

More specifically, it led me to this article on the history of la letra vasca or, as the author coins it, the Basque Renaissance Typeface, a distinctive typographic style characterised by bold serifs and anthropomorphic features, seemingly carved out of stone and harkening to an ancient epigraphic past.

The author, quoting Eduardo Herrera Fernández' in his article, “La letra vasca. Etnicidad y cultura tipográfica,” in the design magazine, Monográfica, explains that the typeface is actually a modern invention, representing the conservative aspirations of a certain group of early 20th century Basque nationalists:

The existence of a Basque typographic character has its origins in the beginning of the 20th century, coinciding with the movement known as “Eusko Pizkundea” (The Basque Renaissance) that developed up until the Spanish Civil War. After this violent confrontation and its consequences of silence and repression, the Basque Country begins a rehabilitative period of preservation and exaltation of the nationalist identity and linguistic conscience. It is for that reason that social and cultural agents contributed, pragmatically, to validate a collective aspiration of recuperation. An array of creative activities were developed with the intention of communal participation in and expression of Basque culture.

The Basque Typeface is… a communal work of art, anonymous rather than having one or more ephemeral authors, and whose style, through a memetic process, has been transmitted throughout generations.

…

Encapsulated in the the Basque Typeface, writes Herrera, “one can find motives for the identification with specific set of values of a political, social and cultural character, and it’s dissemination as a graphic resource results in the very distillation of the nationalism of those identified with protest. This lettering has become the “brand” of a social group and the territory in which it lives, reinforcing a social identity through the confirmation of romanticized origins.”

The except above is merely a small piece of the brilliant article, which goes on to explore why this typeface seemingly lost its typographic monopoly in the latter half of the 20th century, particularly in the post Franco years.

The post is a brilliant mini history lesson of the Basque Country from the late 19th century onwards, delving into the complex history of Basque nationalism, repression, and resiliency.

To continue the architectural tour, let’s chat Basque houses

Like most French regions, the Basque Country has an architectural language specific to the region. Those striking red-painted houses that you likely associate with the Basque region are called etxes (home) or baserris (farmhouse) in local Basque dialect and they have their own weird and wonderful history.

The baserris have been the heart of the Basque culture for centuries, serving as the ancestral home of a single individual family. Traditionally, the household is administered by the etxekoandre (lady of the house) and the etxekojaun (master of the house), who, at a certain age, pass on the home to the most suited of their children (male or female, firstborn or otherwise).

Design-wise, the homes have an amazing amount of cool architectural features that are the result of these unique family lineages. Some of these features include:

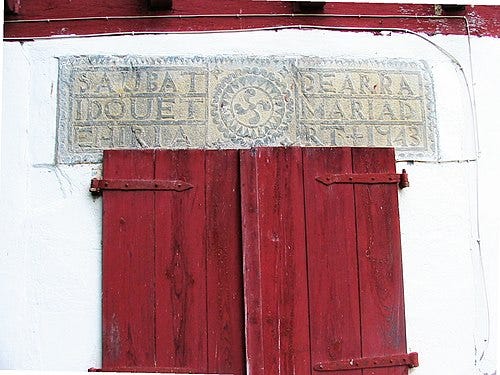

Large stone-carved signs or stones built into the front wall called armarriak (crest-stones) with the family coat of arms

Decorative lintel stones above the entrance called ate-buru or atalburu (door head) which usually captures when the home was built and by whom

Stone carved lauburu in front entryways. Lauburu, meaning “four heads” in Basque, is a swirling cross and is a representation of the Basque Country and Basque people

Half-timbered facades traditionally stained red by using a paint made from olive oil, ochre, and ox blood. Green is also a traditional baserri colour.

Modular floor plans allowing additional wings to be added onto the central structure if necessary

Gabled roofs with extra deep eaves only on the front facade that protect the homes from heavy rain and snow

Three-story structures with stables, the kitchen, washroom, and sitting room on the ground floor, sleeping quarters on the first floor, and produce/food storage in the attic

South-east facing orientation regardless of views to catch the morning sun and shield from harsh Atlantic winds

Interestingly, baserris have not only preserved Basque architectural and design traditions, but have actually aided in preserving the language itself. By passing down baserris intact and undivided through families from generation to generation, the Basque language was protected in periods of persecution by providing the language with a very dispersed but substantial speaker base.

And finally, we find ourselves at Chillida Leku, Eduardo Chillida’s sculpture park

We end our tour in a garden filled with beech, oak, and magnolia trees surrounded by striking sculptures made of steel and granite.

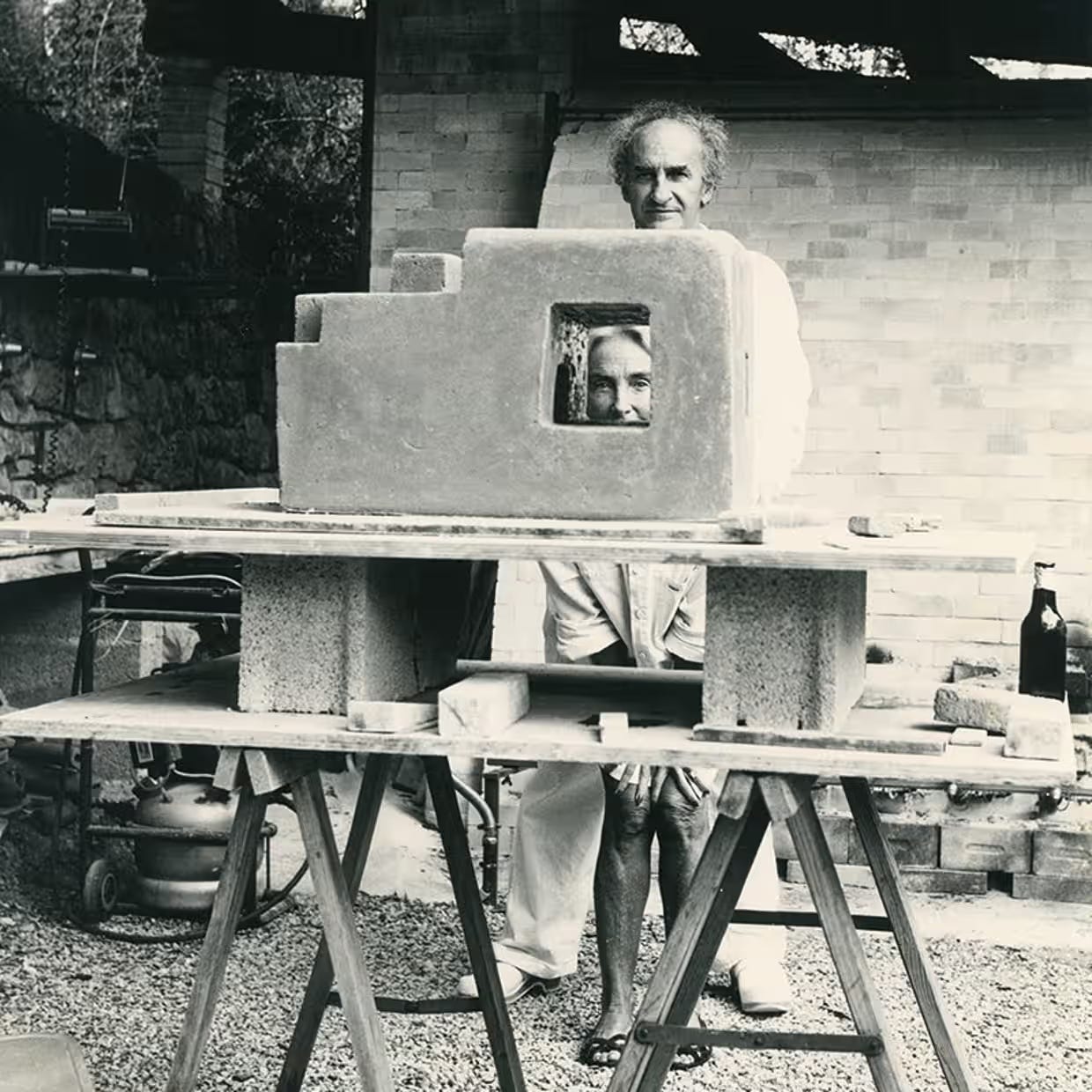

This is Chillida Leku, an open-air sculpture park and museum in Hernani, a small town on the outskirts of San Sebastián, which houses the work of Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida.

The land itself was actually purchased by Chillida himself with his wife, Pilar Belzunce, in the 1980s in order to fulfil the artist’s dream of finding a permanent resting place for his monumental works. The space eventually opened as the Chillida Leku museum where the public were invited to wander through his sculptures amidst the lush greenery of the Basque countryside.

Chillida died in 2002 and, unfortunately, by 2011 his family found they could no longer afford to keep the museum open. Luckily, the contemporary art gallery Hauser & Wirth partnered with the family and reopened the space in 2019.

And what a space it is. The park features 42 of Chillida’s monumental works while a traditional 16th-century Basque baserri (you know what this is now!) houses an exhibition space.

Born in San Sebastián in 1924, Chillida was a promising footballer until injuries led him to study architecture at the University of Madrid. In 1947 he abandoned his degree to make art, moving to Paris where he set up his first studio and began working in plaster and clay.

He is most well known for his monumental, abstract sculptures made from raw materials, notably metal and stone. From Wikipedia:

Chillida's sculptures concentrated on the human form (mostly torsos and busts); his later works tended to be more massive and more abstract, and included many monumental public works. Chillida himself tended to reject the label of "abstract", preferring instead to call himself a "realist sculptor".

Wandering through Chillida’s sculptures at Chillida Leku, you are struck by the artist’s deep connection to the Basque landscape and his unique ability to blur the natural and man-made.

The immense size, random positioning, and general scarcity of the sculptures dotted around the park make them feel as though they are no different than the many trees that have similarly sprung up, happenstance from the earth.

The choice of materials also makes one reflect on the natural passage of time. By using raw materials, Chillida is accepting and celebrating the gradual impacts of time – the process of rust and erosion is not viewed as degradation, but rather as transformation, a sculpture becoming something new, shifting and changing along with the landscape around it.

If you are ever in the Basque Country, please do go visit. It is a magical place well worth the 20 minutes drive from San Sebastián (or you can take the public bus right to the park!).

That’s it for this week! Eskerrik asko irakurtzeagatik (thanks for reading)! ꩜꩜꩜Avery

My heart is beaming while reading this!!!

I still can’t believe my terrible trip timing, but feel confident that I’ll catch you on your next visit here.

I recognize so many spots you photographed and reading this makes me feel super proud and sentimental. And it’s so special that you ate at Hiribarren. What a tremendously unique corner of the world!!❣️